Counting Things

Published: 08/10/2020

Subscribe to Ja3k

That's right this blog is now a newsletter.

Thanks for subscribing!

King Matthias came across a shepherd tending his flock and asked "How many sheep do you have". The shepherd instantly replied 57. "How did you count so fast?" the king asked. "Easy", the shepherd explained, "I simply counted their legs and divided by four".

Hungarian Folk story paraphrased from Babai's telling.

.

Counting with Bijections

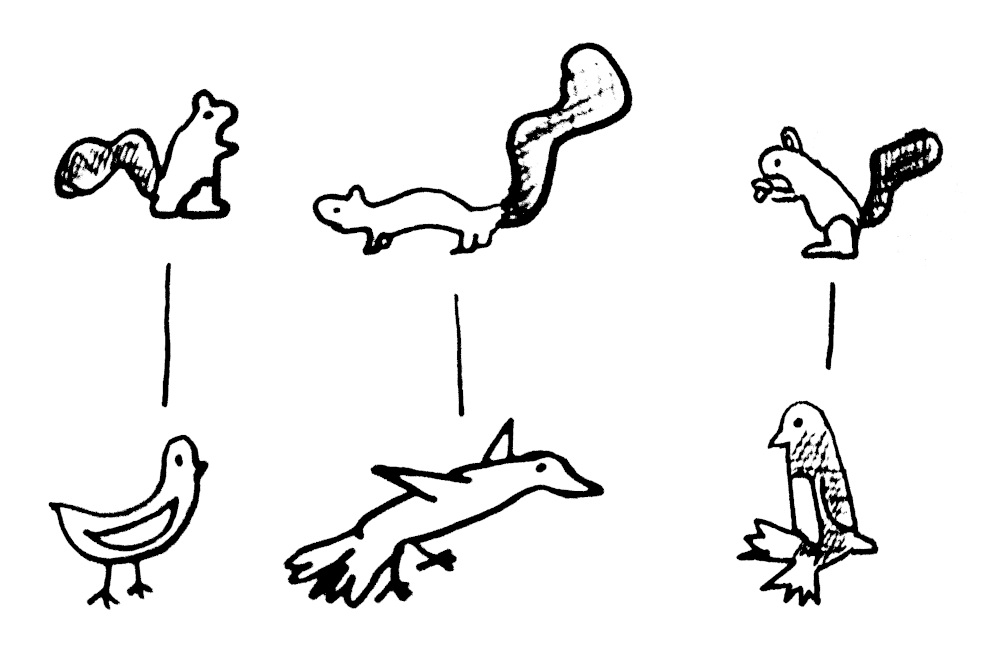

A basic problem, the basic problem, in mathematics is to count things. Of course we all know how to count things. We point at the objects we're counting and say "one, two, three ...". Or if we're not in kindergarten we probably keep our mental processes mental. But the idea is the same: We associate the objects we're counting to numbers and the largest number we reach is the number of objects there are. This technique of counting: 'laying our objects next to our numbers' Can be adjusted in the following way: 'lay our objects next to some other objects'. This won't tell us the number of objects we have. But it will tell us if our two groups have the same size and if not, which is larger. Here we have the same number of squirrels and birds.

An association between two sets where all the elements of the two sets are uniquely paired off with no elements left over is called a bijection. If after pairing off one of the sets has a few elements left over then it is called an injection from the smaller to the larger set.

Of course the power of this method isn't exhibited when the sets are of three elements. But this technique can allow you to do things you couldn't do easily by counting. In a ballroom of paired heteronormative dancers one can immediately know there are as many men as women without needing to count them up. One can deduce there are twice as many hydrogen atoms as oxygen atoms in a glass of water by considering the association of pairs of hydrogen atoms to an oxygen atom [1].

These considerations become essential when we can't count the elements of our set by pointing at them one at a time. Maybe we're counting a set which is delimited by a parameter. Or maybe our set does not have a finite number of elements.

Exercise: How many non-decreasing functions from a set of size n to a set of size m are there?

Solution: This is the same as the number of strictly increasing functions from to given by the bijection . This set is further in bijection with subsets of size in . This bijection is given by taking the image.

Bijective proofs are some of the most beautiful things in combinatorics. For more consider:

- Exercise: How many ways are there to put n identical balls into m identical buckets? (hint: google stars and bars)

- Exercise: Prove that the number of partitions of n with distinct parts equals the number of partitions of n with odd parts.

- The pentagonal number theorem

But the real power of our method isn't even demonstrated in exploring these schemas of sets. In theory for any fixed n and m, say 10 and 100, one could write down all the non-decreasing functions from 1..10 to 1..100 and 1..10 to 1..109 and see that there is the same number. But what if one wanted to compare sets of infinite size. We'll never finish counting the natural numbers up in order to compare them to the integers. But we can describe an association of the natural numbers to the integers. Just send the odd naturals to the positive integers and the even naturals to the negative integers.

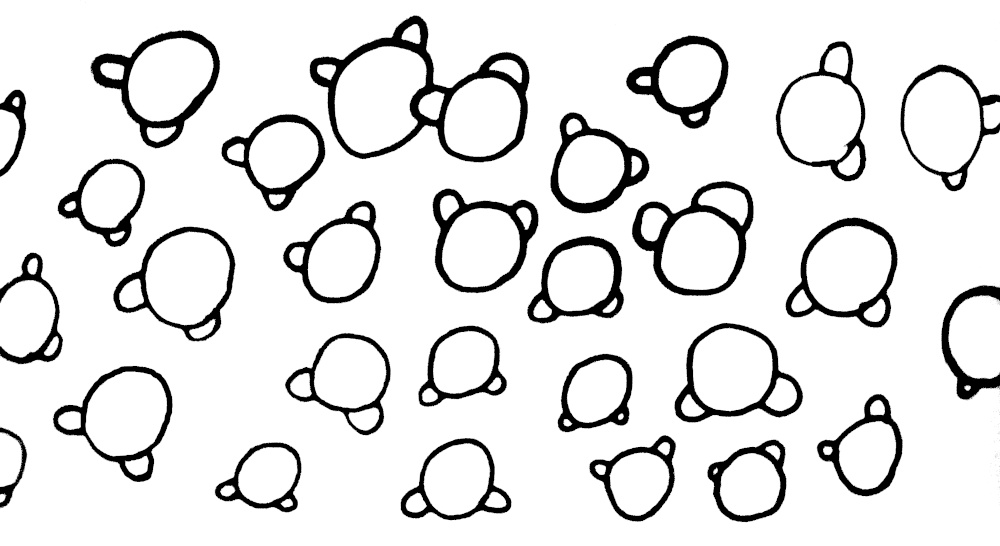

This both makes sense and is very confusing. They're both infinite so one might expect them to be the same size. But also the naturals sit inside the integers. So one might expect the naturals to be smaller. To this second point observe this alternative definition of an infinite set: A set is infinite if and only if it is in bijection with a subset of itself. If I have a finite number of things, no matter how I move them around, I'll still have the same number of things. If I have three cups and three balls no amount of fiddling will leave me with all the balls in cups, no cup having more than one ball and an empty cup. Not so with infinite sets! Consider the classic example of Hilbert's Hotel. Imagine a hotel with infinitely many rooms, each occupied. A new guest arrives and asks if there is room. The doorman says yes, we'll simply move the guest in the first room to the second, the guest in the second to the third, and so on.

yes

Have any room?

yes

One might start to suspect, fiddling around with some infinite sets, that there is only one class of infinite sets and they are all in bijection with each other. But given any set, finite or not, I can construct a new set which is larger. Consider a set and the set of all subsets of , called the power set of denoted . Suppose we had a bijection between and . So each in is associated to some subset of . It could be the case that is in or not in . Consider the subset of which contains those which are associated to subsets of which don't contain them. Call this subset . We cannot have because if is in then is not in and if is not in then is in .

Of course the natural numbers are the smallest infinite set. Consider another infinite set and start enumerating it's elements. If you ever run out than it was in fact finite. So we have a surjection from that set onto the naturals. With that in mind we call an infinite set countable if it is bijective with the naturals. Otherwise we call it uncountable.

This is very similar to Cantor's original diagonalization argument which shows the real numbers are larger than the naturals. I like this argument because it doesn't assume anything about the existence or structure of the real numbers. It also goes all the way up. It shows that the reals are larger than the naturals (once you've convinced yourself the reals are in bijection with the power set of the natural) and it shows that there are larger sets than the reals. And indeed there is no ceiling.

Exercise: Show that the real numbers are in bijection with the power set of the naturals (Hint: the next section may help).

Something that's always seemed a little funny to me about this proof is that here we are comparing these two, huge, possibly infinite sets, and we show there cannot be a bijection by finding exactly one element which is not mapped to by our bijection. In principle there must be many. For finite sets of size we know there are . For infinite sets by our example of Hilbert's hotel we know there must be infinitely many. In fact the number of elements which are not mapped to must have cardinality greater than the original set. But we just find one element that isn't mapped to and that suffices. It's very economical.

The Continuum Hypothesis

We've seen the power set of an infinite set is larger than the original set. The natural next question is: are there sets in between. This question is the subject of the continuum hypothesis. The continuum hypothesis states: There are no sets strictly in between in cardinality of the naturals and the power set of the naturals. One can also ask if there are sets in between the power set of the power set of the naturals and the power set of the naturals and so on. This is called the generalized continuum hypothesis.

The generalized continuum hypothesis turns out to be independent from ZFC. There will be more on ZFC later but basically this means there can be models of sets where the continuum hypothesis does and does not hold.

I don't really have any intuition about what the truth of the continuum hypothesis should be. Gödel believed that the continuum hypothesis or its negation would eventually be observed to be a corollary of a more intuitive axiom. But I'm skeptical of that. It seems not much in mathematics or the physical world should depend on this question's truth. Though maybe my sense that these things are independent reflects a lack of imagination. Maybe mathematics took a wrong turn and we should all believe in the Axiom of Determinacy instead of the Axiom of Choice.

The Cantor-Shröder-Bernstein Theorem

In the previous section I've freely described sets which inject into another set as smaller than or equal to that set. And indeed for finite sets that makes sense. But we've seen for infinite sets you can rearrange them to strictly sit inside themselves. One may worry that we could have two sets, both of which can be rearranged to sit inside the other, but which in no way can be rearranged to lie side by side. Luckily the CSB theorem says that cannot happen. Note the theorem got its complicated name through a series of independent (some incorrect) proofs. Maybe Dedekind's name should be in their somewhere too.

The theorem states if injects into and injects into then there is a bijection between and . Let's name the injections and .

We can construct a bijection by following our noses. Let's start with an in and iteratively consider . This chain either consists of infinitely many unique elements or eventually repeats from . If it ever repeats, say then by the injectivity of and we can strip off the outer 's and 's to get .

Suppose the forward chain never terminates. Then let us go backwards. It could be that some element of maps to and then some element of maps to that element and so on. Because of the injectivity of and those elements are unique if they exist. We're not guaranteed to be able to go backwards and at some step of the process we may fail, at either or . Or the process could go on indefinitely. So we have four cases for our chains,

- A loop,

- A bidirectional infinite chain,

- An terminated chain,

- A terminated chain,

These four cases partition all the elements of and into chains. Each element of and falls into exactly one unique chain. So we have simply to describe a mapping on elements of for those that fall into each of these chains in such a way that it's clear we get all the elements of .

- For loops just keep our original mapping .

- Same for our bidirectional infinite chains. Just map with .

- Same thing if we have a one sided infinite chain ending in .

- One sided infinite chains ending in are the only case where we need to do something different. Simply push everything backwards. The inverse is defined for the elements of in these chains.

One should check that every element of is indeed mapped to by some and we have our bijection!

The Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem

This section will be a little more hand wavy than the earlier sections. To really be precise here one would have to develop model theory and the theory of first order logic, which is a little beyond the scope of my casual blog. But I think the theorem is interesting enough and relevant enough to the understanding of infinite sets that I would like to say something.

Basically we have models and we have theories. Models are the mathematical object itself. Suppose I tell you I have the natural numbers. You ask what that means. And I explain, "well there's 0, 1, 2 ...". Theories are a set of sentences describing the mathematical object. I tell you I have the natural numbers. You ask what that means. And I explain, "Well there's a first element. And for each element there's a successor. And the successor of an element is never 0. And every nonzero element is the successor of some element".

Basically there are two ways of thinking of mathematical objects. One can think of them as existing as some set somewhere. Or one can just have a system of statements about the object and try to deduce things from there. For example one can reason about Groups as a collection of symmetries or as an object satisfying some axioms. Both perspectives are valuable.

Let's look more carefully at the sentences I used to describe the natural numbers. Notice this set of sentences don't uniquely describe a mathematical object. For example the disjoint union of the natural and the integers satisfy all those sentences. So you might complain that I missed an important sentence, "every element can be reached by taking the iterated successor of zero". But that sentence can not be written down in first order logic. It is the conjunction of infinitely many clauses: All naturals are either 0 or the successor of 0 or the successor of the successor of 0 or ...

In first order logic all our sentences are finite and built up from or, and, not, for all and there exists. So any first order theory of the naturals which only knows about and succession (as opposed to also knowing about addition, and multiplication etc.) will not be able to distinguish the naturals as we think of them from these other mathematical objects.

It turns out this example isn't an exceptional case due to our under specified theory but the general phenomena.

Theorem (Löwenheim-Skolem) A first-order theory which has an infinite model has an infinite model of every infinite cardinal.

In our example of the naturals we could take any number of copies of the integers. We need the condition that there are some infinite models because for example our theory could have a sentence which says "every element equals 0" in which case there would only be finite models.

This theorem seems to say something paradoxical about sets. We observed earlier that there are infinite sets which are not bijective. But sets are usually understood to be axiomatized by the Zermelo-Fraenkel with Choice (ZFC) axioms [2]. The important thing is that ZFC is a countable first order theory. So if there is a model of ZFC [3] then there there must be infinite models of every cardinality, in particular there must be countable models. But we've already seen that we can infer the existence of uncountable sets from axioms of set theory. So what gives?

One interpretation is that ZFC is really something very weird. We may give the axioms human understandable labels like 'This one says there is an infinite set' and 'this one says you can take the power set', but really the axioms say what they say, and we hope one of their models captures our intuitive notion of set but some of its models are quite exotic and unintuitive.

I like to take it as emphasizing that we didn't show that the power set of is 'larger' than . All we showed is that there is no bijection between them. Maybe they both sit inside some countable model but we just don't have enough functions in our model to map them to each other. Maybe the hierarchy of infinities doesn't say something about the abundance of infinite sets but about the relative paucity of functions we have on hand to map them to each other.

[1]: This is an approximation. Based on the acidity of the water there may be a surplus or deficit of hydrogen, and there may be oxygen molecules dissolved into the water.

[2]: The axioms say nice things like: one can take power sets, unions, set differences, subsets, the set containing two other sets, the image of a set under some function. And also that sets are equal if they have the same elements, a set contains an element from which it is disjoint, there is some infinite set, and the arbitrary product of nonempty sets is nonempty.

[3]: For there to be a model of ZFC it must be consistent. But if it is consistent its consistency is independent of ZFC. So in so far as ZFC captures mathematics for you the fact that there are models of ZFC must remain open. But it seems likely to me that it is consistent.